Watch a swarm of drones autonomously track a human through a dense forest

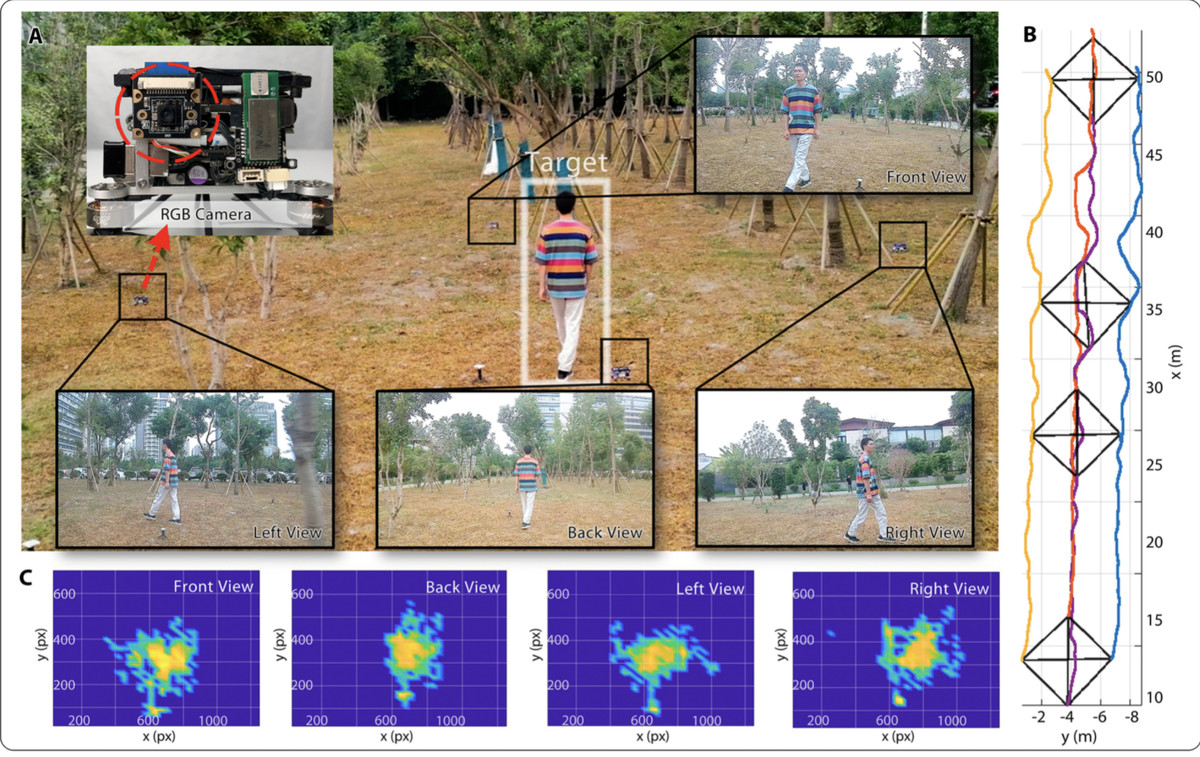

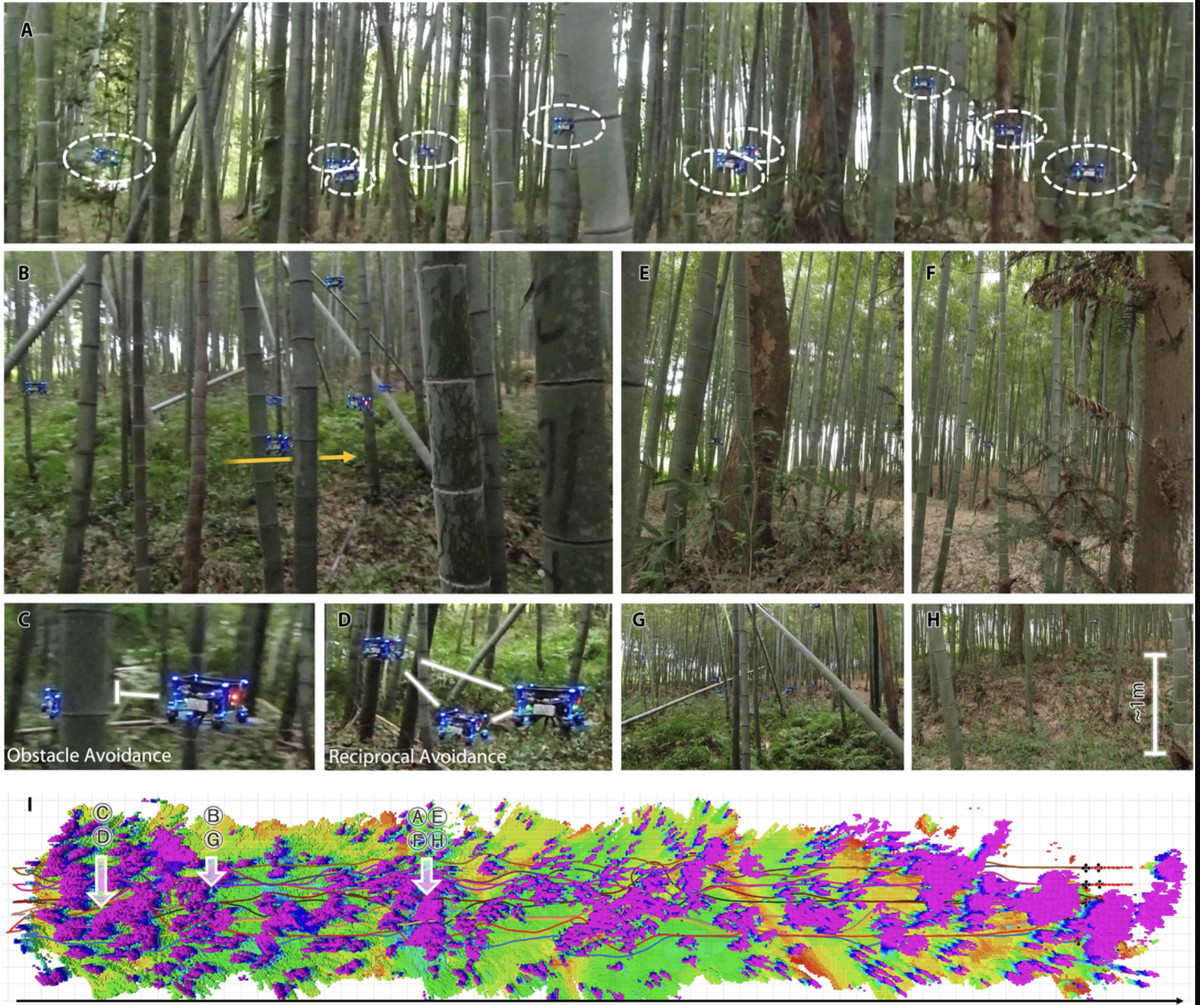

Scientists from China’s Zhejiang University have unveiled a drone swarm capable of navigating through a dense bamboo forest without human guidance.

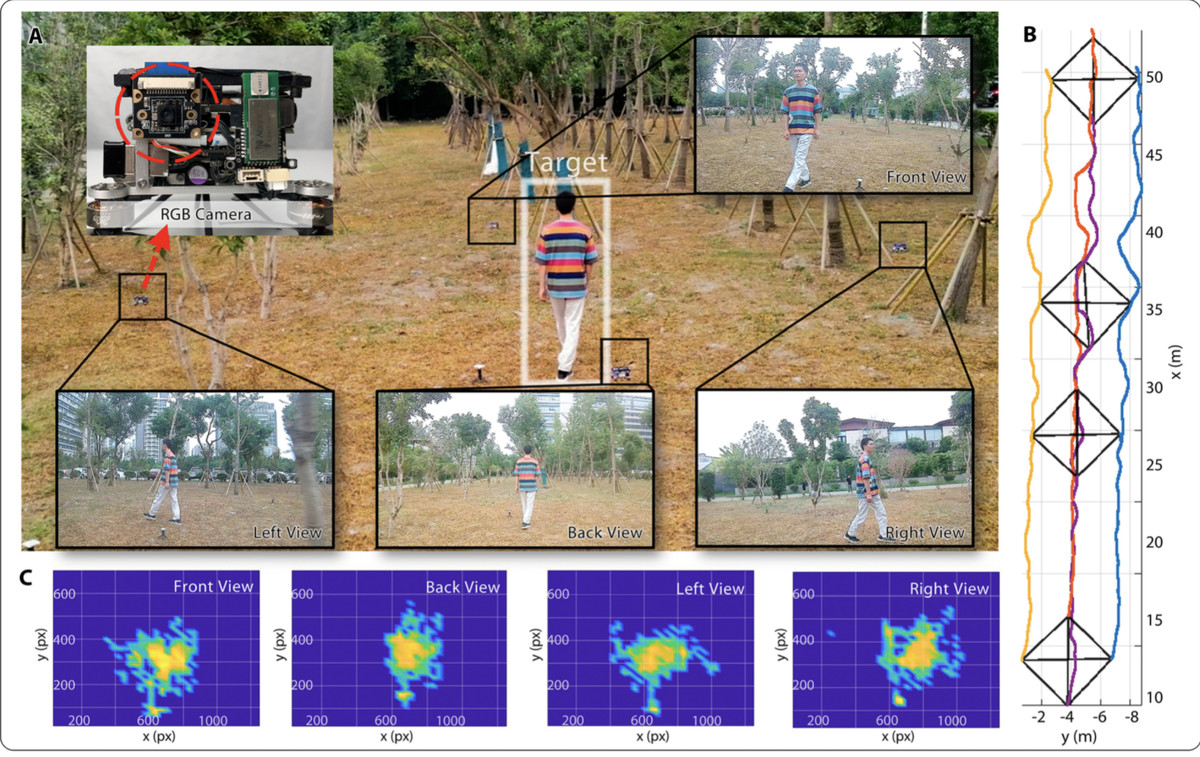

The group of 10 palm-sized drones communicate with one another to stay in formation, sharing data collected by on-board depth-sensing cameras to map their surroundings. This method means that if the path in front of one drone is blocked, it can use information collected by its neighbors to plot a new route. The researchers note that this technique can also be used by the swarm to track a human walking through the same environment. If one drone loses sight of the target, others are able to pick up the trail.

In the future, write the scientists in a paper published in the journal Science Robotics, drone swarms like this could be used for disaster relief and ecological surveys.

“In natural disasters like earthquakes and floods, a swarm of drones can search, guide, and deliver emergency supplies to trapped people,” they write. “For example, in wildfires, agile multicopters can quickly collect information from a close view of the front line without the risk of human injury.”

However, experts say the work also has clear military potential. A number of nations — most prominently the US, China, Russia, Israel, and the UK — are currently developing drone swarms that could be used in war. Militaries tend to invoke surveillance and reconnaissance as the most common applications for this work, but the same technology could undoubtedly be used to track and attack both combatants and civilians.

Elke Schwarz, a senior lecturer at Queen Mary University of London whose specialisms include the use of drones in combat, says this research has clear military potential.

“The capability to navigate cluttered environments, for example, is desirable for a range of military purposes, including for urban warfare,” Schwarz tells The Verge. “As is the ability to ‘follow a human’ — here I can see how this converges with projects that seek to develop lethal drone capabilities that minimize risk to on-the-ground soldiers in urban environments.”

The recent war between Russia and Ukraine has shown how quickly drone technology can be adapted for the battlefield and what a devastating effect it can have. Both sides in the conflict are using cheap consumer drones for reconnaissance and, sometimes, offense. One method involves using drones to drop grenades onto opposing forces. A recent video showed Ukrainian troops using what appears to be a DJI Phantom 3 drone (price-tag: $500) to drop a grenade through the sunroof of a car supposedly driven by Russian soldiers.

What makes drone swarms potentially more dangerous than lone machines, though, is not just their numbers but their autonomy. No single human can simultaneously control a swarm of 10 drones, but if this task can be offloaded to algorithms then military planners are more likely to embrace the use of this sort of autonomous system in war.

Currently, drone swarms are limited in their application. The most common real world use-case is creating elaborate light shows. But in these scenarios, drones are following preset trajectories in open spaces, using tracking technology like GPS to locate themselves.

The research from Zhejiang University advances on this by using only on-board sensors and algorithms to control the drones’ flight without prior mapping of their environment. “This is the first time there’s a swarm of drones successfully flying outside in an unstructured environment, in the wild,” Enrica Soria, a drone swarm researcher at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Lausanne, told AFP. Soria added that the work was “impressive.”

In their paper, the scientists note that approaches to drone swarms tend to follow one of two programming paradigms: either “bird” or “insect.” In an “insect” swarm, the focus is on fast, reactive movements that require less forward-planning while a “bird” swarm tries to direct drones along long, flowing paths (the latter being the researchers’ approach). Both methods have their trade-offs, as thinking like an insect requires less computing power, but planning like a bird is more energy efficient. But, as the computing capacity of hardware improves, programming bird-like behavior has become more attainable.

Schwarz notes that although the focus in such drone swarm research is often on these technological achievements, this can obscure the trickier questions of how such work should be deployed. She cites the observations of 20th century US mathematician Norbert Wiener, whose work laid the foundations for AI development.

Says Schwarz: “[Weiner] said — in the 1960s — that there is a disastrous focus on and obsession with ‘know-how’, which tends to eclipse the moral question we should be asking: what is it good for.”